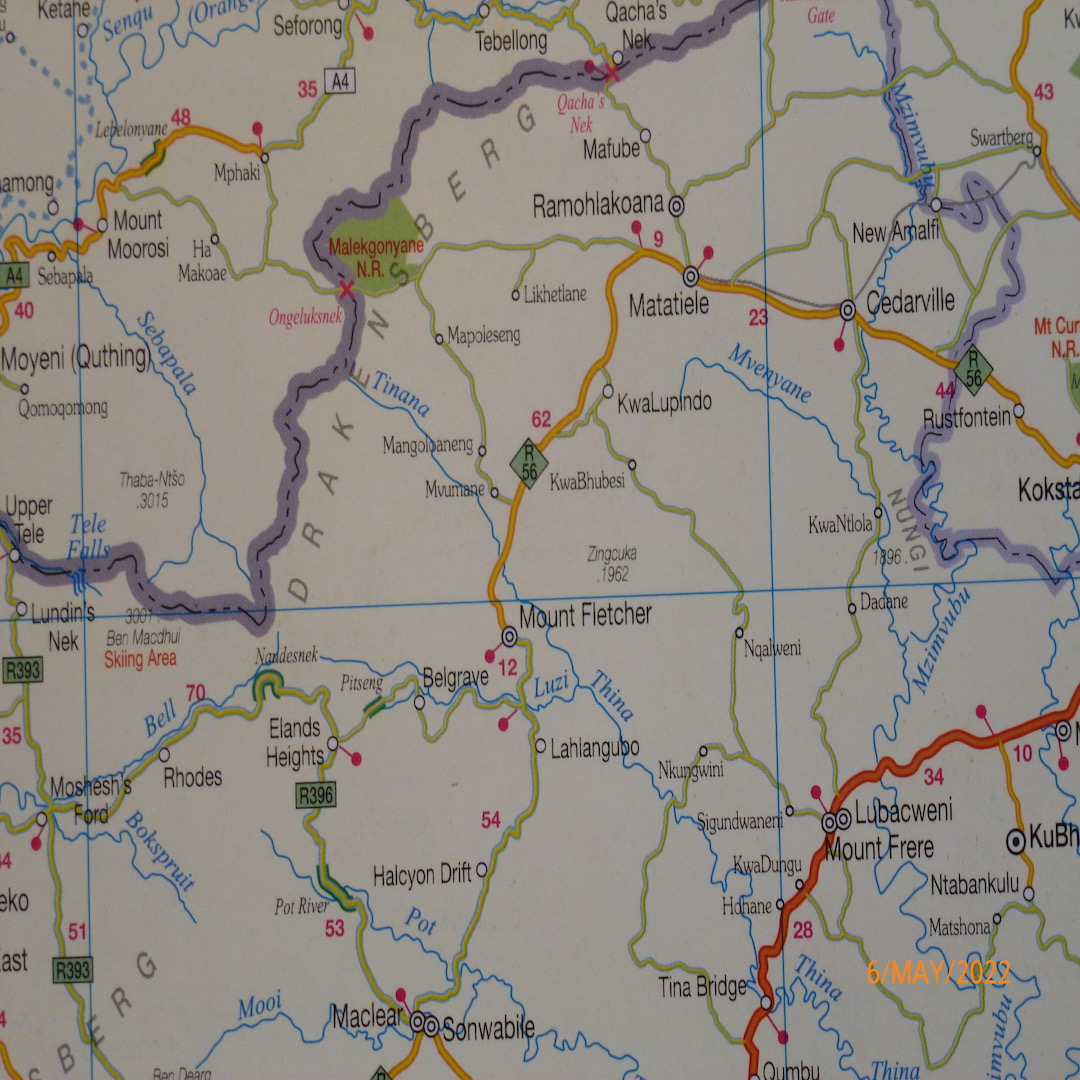

The road from Kokstad to Matatiele is the R56 and despite its elegant number, it is winding and narrow. It runs north-west from the province of Kwazulu-Natal, generally known for its sub-tropical climate, to within 45 kilometres of the high Drakensberg Mountains, which separate South Africa from Lesotho. Winter here is bitter and at ten o’clock at night, with snow falling as ice particles on the windscreen of the car, it is worse. And this is where my story begins.

It is not unusual to see a lone walker on any road between small towns at any time. There are turn-offs to tracks to the left and to the right at regular intervals, and to me, they remain enigmatic but alluring. I know for example, from having driven along this road many times in daylight, that there are settlements up in the distant hills and deep in the valleys.

This particular night, however, the surroundings felt different. My headlights illuminated an old man with a stick. He was leaning against the wind and steadily limping in the same direction as my car, along a rare straight section of the road. He did not falter or turn. He simply moved forward as though his pace, his familiarity with the road’s edge and his tucked-in head and shoulders, were all he needed for comfort and purpose. I drove past him – 200 metres, 500 metres, one kilometre. I saw no turn to the left or to the right. I slowed the car down and turned it back in the direction from where I’d come. A minute later I saw the old man, still steadily progressing like a snail on a leaf, or a tortoise in a cabbage patch, undisturbed as though ignorant of all adversity. I searched for his face as I passed him. His eyes remained focused on his stick and his footsteps. All else seemed superfluous.

Again, I turned the car and slowly came up to him for the second time. I lowered my window, felt the severity of the cold on my bare hands and face, and shouted a greeting in the language of Southern Sotho. He turned, raised his hand, his stick hanging from it, and smiled with no words. Standing in front of him with my back to the deteriorating weather to protect his now exposed face, I asked him to get into the car.

‘Thank you,’ he replied in formal South Sotho as though respecting a chief, ‘but no. I have legs that won’t bend and I need to walk.’

Matching the formality in his language, I asked him to come to the back of the car.

‘I will make a plan for your travel,’ I said.

He leaned back against the loading platform of the estate car, his stick stowed beside him and his hands holding either side of the inside of the body of the car, with the rear door wavering in the wind above him. Kneeling in the car behind the front seats, I gripped his armpits and pulled him towards me, while he pushed with his hands and elbows until his weight was off the ground and his body, supported by his hands, was securely inside. I knelt on the front seats, completed his installation and closed the rear door.

More exhausted from the manoeuvring than his walking, he closed his eyes and leaned back against the back of my seat, our heads touching while I drove.

‘Don’t sleep,’ I said, ‘I need you to tell me where to turn off.’

He waved his hand to acknowledge me. The wipers went back and forth taking a thin layer of ice with each swish.

‘Is it here?’ I asked after three kilometres.

I watched his hand move side to side in dismissal in the rear view mirror. At three and a half kilometres I saw the same dismissal. At five kilometres I saw his raised hand, signalling me to stop.

‘OK,’ he said in English. I looked at the track leading uphill to blackness.

‘You’ll have to get me out now,’ he said. ‘I’ll walk from here.’

‘I’ll get you home,’ I replied.

‘You cannot in this,’ he said referring to the car.

‘You OK if I take a chance?’ I asked.

He acknowledged my dare with a slight chuckle, which I accepted as permission and as a challenge.

Backing the car from across the road gave me four or five car lengths before the track’s incline. The old man braced himself against my seat and the rear door as I showed him. I began the incline at speed, with wheels spinning and the engine screaming. I didn’t let up until I topped the hill after two kilometres. The noise forewarned the occupants of three huts of our arrival. They now stood huddled in their doorways watching, while I opened the rear door and helped the old man out. An old woman screamed and ran towards the old man and hugged him and hugged him and hugged him. She took his stick from me and hugged me. Tears ran down her cheeks. Others gathered about the old man making him appear less stuck to the ground.

‘Come in, come in,’ said the old woman. As graciously as I could, I refused in my best South Sotho, telling her honestly that my parents would be worried. The old man asked all the people, including his wife, to go inside their huts and close their doors before the cold reached in. Only when he looked towards his own door, did the old woman close it.

He turned to me and reached for my right thumb with his right hand and I did likewise.

‘You’re a good man,’ he said. ‘I knew I would die tonight and you also knew, but you didn’t let it happen.’

H. E. Roffey